Robert Ruark once reminded his readers to ‘carry enough gun’ when in search of dangerous game. I returned to England on a wet August day this year to hear that a chap guiding a photographic safari in Zimbabwe had just been killed by a lion and another, a few miles away, was trampled by an elephant.

While ‘Cyril’ the lion seemed to have ‘gone viral’ while we were away, deaths in the bush like these go largely unreported in the European press. The underlying truth of hunting in Africa is that dangerous game hunting is just that: dangerous. Africa can mess-up your day very quickly if you are in the wrong company and unprepared.

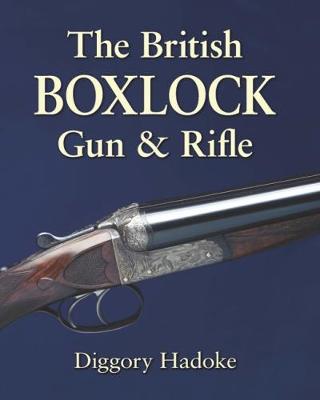

We headed into Tanzania’s Rungwa Game Reserve, planning to tangle with some serious beasts on their own turf and had planned a suitable arsenal. Our big game rifle was a brand new Westley Richards .577 nitro express. The design dates back to Deeley & Taylor’s 1897 ‘drop-lock’ version of Anson & Deeley’s ‘boxlock’ action.

The .577 throws a 750 grain Woodleigh bullet, either soft-nose or solid, at around 2050 feet per second. It was sighted-in at 50 yards at the Westley Richards underground range but the forte of these big, open sighted double rifles is closer. As close as you can get. The idea is to stalk in until you can hear the animal’s snorts and grunts before felling him on the spot. If he winds you and comes, you have the power in your hands to put him down in his tracks.

This may all seem rather unnecessary. Why not shoot a buffalo off sticks with a ‘scoped .375? The answer is that a buffalo is not dangerous at 80 yards; unless of course, you wound him and have to follow him into the long grass! To my mind, if you want to hunt dangerous game, let it be dangerous, otherwise you may as well just shoot deer.

The first opportunity to test the new rifle came on our first day in camp – Westley Richards’ production manager, ‘Trigger’ and I were out looking around to scope-out the country and the likely quarry, when we spotted a pair of old buffalo bulls edging away into the long grass. We got on their trail fast, with our Maasai trackers leading the way. This was grass burning season and a grass fire cut off their retreat, holding the animals up in a section of thick bush. They seemed totally disinterested in the burning vegetation, common as fires are here. They also showed no interest in breaking out into open ground. So, we went in.

Trailing the black shapes into the grass tunnels gets the heart beating. Buff weigh 1,000 lbs plus and have no sense of humour. Fortunately, a termite mound provided some elevation, giving us a partial view down onto the grazing bull, perhaps twelve yards away. Without hesitation, Trigger levelled the Westley Richards and fired; the buff stepped forward half a yard before the second bullet slammed home, then dropped on his face in the grass. His companion glared at us. Would he come? After a standoff, he moved away and we approached the fallen one. No drama, no fuss, dead as the big, black rock he resembled.

The second of our encounters was a single old ‘dagga boy’ spotted early morning, as he crossed a patch of low scrub, towards more cover. We began the stalk from 500 yards, using the steady, morning south-easterly to our advantage. The wind stayed in our faces, the old buff had no idea we were there, allowing me to stalk in quietly to ten yards. He stood in the long grass, head down, grazing.

As I turned to raise the .577, a spear of grass jammed into my right eye, blinding me for an instant, then filling with fluid, blurring the vision I had. Blinking the pain away, I cleared enough to home-in on his ‘boiler room’ and fire a soft into his lungs, the big bullet apparently breaking his spine as it traversed the huge body, for he dropped on the spot, legs collapsing and head rearing upwards just enough to allow me to put a solid from the left barrel through his ear. He never twitched.

Many writers dismiss the .577 as a cumbersome, unnecessarily powerful beast of a rifle. I beg to differ. A properly made rifle in this calibre, weighing about ten and a half pounds, with 24” barrels and perfectly balanced, is the best medicine when you are up-close and personal with dangerous game. The security you feel with the big boomer in your hands is multiples of what you get with more common .375s or .416s. They will do the job. They are superb calibres, but there is no substitute for horsepower when you can smell their breath. As our host, veteran PH Danny McCallum, reflected, as he lit a cigarette and admired the rifle while the skinners got to work “She certainly speaks with authority”. She does indeed!

Published by Vintage Guns Ltd on (modified )