On June 3, 1910 John Aloa Jameson, from Dublin, Ireland attended a dinner meeting of the Shikar Club at the Savoy Hotel, The Strand, London. Also in attendance was Frederick Courteney Selous, from Mashonaland, South Africa.

The last course had been served, reports and papers read, the lectors applauded and departed as a deepening twilight spread across the city of wealth and power. Among the deserted tables five of the “Shikar” group converged on south windows in the Savoy dining room looking out on a broad bend of the upper Thames, drawn to the river not for itself, but for the great distance into which it flowed. That current had seen each of them depart and return on their schemes of adventure and wealth.

As though by appointment they arranged themselves to commune with their river, seated for easy conversation, enjoying a last brandy and cigar. The Civil Servant on leave, just in from Bombay, sat to the left of J. A., while a cousin sat to his right looking east toward the sea reaches and the ebbing tide. The Trading Firm Director leaned against a window frame watching steam tugs moving easily with the tide, prepared to meet returning ships of trade coming in with the morning flood, their cargoes intended for the city’s shops. The evening was quiet, low sounds from the Strand recalled murmurs of an equatorial village as it quieted for the night. Introspection seemed the order of dusk until JA voiced the start of a memory.

“We outspanned in late afternoon,” JA began, “without benefit of a weekly paper, giving us a few hours for reflection induced by our days’ work. Selous and I had well over a year of evenings for reflection and talk.” “We spoke of travel,” JA recalled, “of native people and paths, of vegetation and the lay of the land, of how it all began, where it had carried us, of youth’s fantasy and harsh reality, of horses and wagers, fishing and hunting, of Scotch whiskey and Irish distillation, dry flies, rifles, and cartridges.

We talked, painting the many images of our moveable lives. Never at home, always pointed to a blank spot on the map, we were content to know the geographic relation of the next village, the immediate country through which we trekked, and perhaps a bit of news concerning a close relative received in a letter at a forgotten interior station.” JA’s voice became low, as though lost in a return to those other conversations and the quiet of the evening. His introductory comments drew us into his disquieting tale.

“An ox train moves slowly,” he continued, “not aware of its destination, much like a complex idea through a primitive mind. We did not wish to belabor the familiar personality of oxen, so we spoke of travel by other means, by steamers and sail, by Concord stage, by Indian howdah, most frequently by saddle. We shared a dependence on horses for close survey of our routes, much preferring saddle to boot. I knew the horse following hounds on a crisp winter day in County Neath above Dublin, or threading a narrow trail into the Judith basin, Montana Territory. Selous knew the horse searching for an approach to rugged escarpment dividing Zululand from the Natal.”

A whisper interrupted JA. “What did you say?” He asked. “‘Simple matter of experience round the stables!’” “No! Such is the experience of dullards with only placid stable knowledge. We had experienced every mood of a horse in wilderness, without a saice close by. We both knew what a horse could do and, more important, what a horse would not do out there. Such knowledge was required in the work we were about.

During the day, after the wagons inspanned, we saddled our horses, took up our rifles, set off on a “ride around,” through foreign territory on opposite sides of our path, learning the convoluted slopes of the land, looking to hunt up a brushbuck, or, if lucky, an eland for our meal at sundown. As much as we relied on our rifles, we were dependent, you see, on our horse’s sense for the continuously alien ground over which we rode. We trusted the horse knew how to move quickly without placing a hoof wrong. How to stand quiet as we took a shot at game. The first day in the saddle showed us how well we could rely on our mounts.

I had heard of Selous’ ability with rifle, horse, and wagon, but faced with the scope of the trek could not rely completely on a reputation. My trust improved as we set off on our daily search for game, as I watched him work among the drivers, deal with complaints from porters, struggle with ox and wagon, making that trek through the south African interior. In those days Frederick Courteney Selous was a hunter and a trader, he hunted to trade and traded to hunt.

He dealt in basic goods, fresh game for isolated villages, cloth and beads, salt and copper wire, and took in trade feathers and hides and ivory for sale on the coast, destined for the tastes and fashions of this city. He had come out as a lad and returned home on few occasions. His knowledge included wide readings in literature and history, years of experience with this uncertain life beyond the coast, the languages and mystifying politics of the interior, the lay of the land, and the ways of its’ people and its’ game. That knowledge was extensive, helping him survive in a foreboding wilderness.

I had also journeyed far, first through the western steppes, Montana and Wyoming Territories, then to the far east through Bombay to hill stations in Kashmir, and finally to Africa. Even at home on the Isle, I searched out salmon and trout streams. Twice I took my brother James on memorable passages to Montana for the land, the hunt, and a bit of fishing in clear mountain streams. James and I were as close as twin brothers, sharing a love of the outdoors, primitive country, and sport.

We were close in our love of the wilderness, the uncertainties of the hunt and in our tastes for a best rifle. We used our rifles hard, adjusting our specifications to gain the best weapon for the game and the harsh travel required. And we purchased our rifles through our Dublin Rigby shop, took delivery of the shop’s products in Dublin, London, Bombay, South Africa. For hunts in Montana, we had Rigby 360 rifles, entirely suited to the game of that country. James continued with the 360 and a 400 Rigby, but I began thinking of something more for travels to the east, a 400 express at least and perhaps a 500-450 from Rigby.

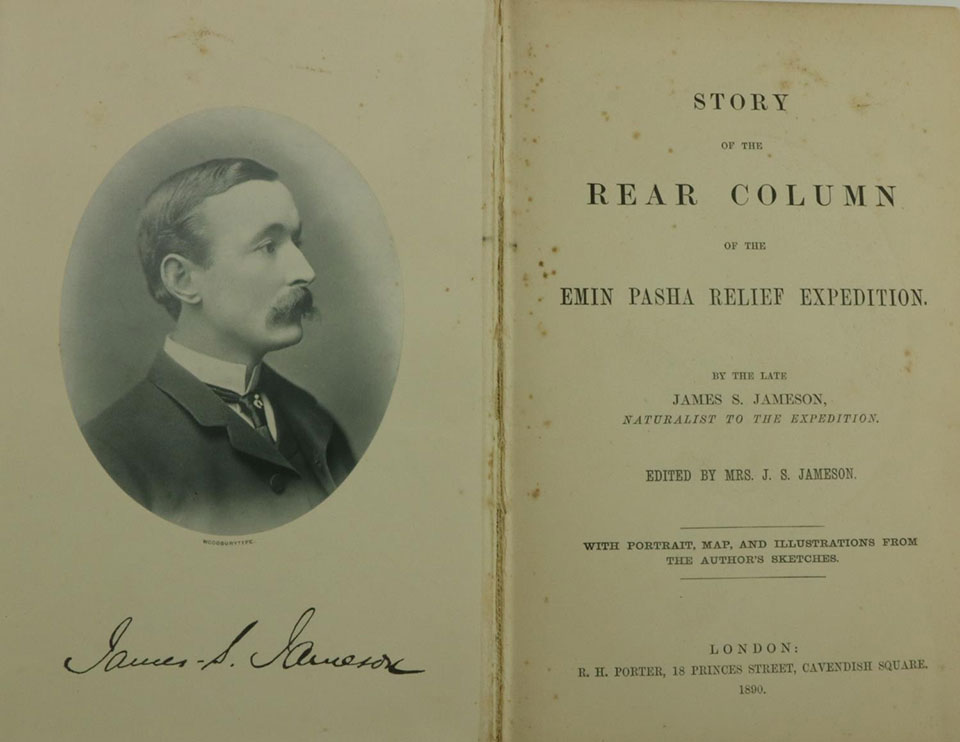

As my urgings brought James to Montana, James was the inspiration for my passages to Bombay, Kashmir, and Africa. James was ever the naturalist, searching relentlessly through India, Borneo, and Africa’s Mashonaland, for birds native to those far corners of the empire. My brother was a faithful disciple of Darwin, precise in his descriptions of specimens, meticulous in their preservation. His collections went to Kensington, the Natural History Museum, for edification of the public. They were quite well received and lauded for their beauty and style.”

A faint murmur disturbed the evening quiet. “You mutter, ‘posturing?’” JA asked, “’Posturing?’ Indeed, since his tragic end James has been severely criticized in the press as a ‘whiskey mogul’s son posturing in an age of science.’” “That error must be corrected!” JA countered. “My brother did not live an illusion in his travels and certainly did not go about his work on a whim. Look at the studies James did in the lands of the Ndebele with Selous in ’80, ‘81, the extraordinary variety of specimens James cataloged for the Zoological Society. Read the diary of James’ last advance up the Congo to see the measure of my brother.

James joined Stanley’s expedition as its’ naturalist, intent on detailed scientific exploration of that watershed. His diary clearly reveals the odd nature of Stanley’s strategy and James’ recurrent frustration not being given latitude for a full naturalist’s examination. No, James was not ‘posturing’! He searched! And he bore with the inanity of command.” JA’s intensity cut with a razor edge. We were stilled for a bit, not daring to oppose his outburst, as the inaudible night slowly took some bite from his voice. When he began again the tale took an unexpected turn.

“Unlike my brother, I could be accused of a bit of posture.” JA confessed. “Where I travelled, I simply went for the hunt. It is expected of a gentleman. I had the means to go, so I went, Rigby in hand, to Montana for elk, antelope, grizzly, and sheep, to India for tiger and buffalo, and to Africa for its’ varied game.

It was James, in his quest for the rare species, who first became acquainted with Selous in the Matebeli country. It was James who introduced me to Selous. Selous’ opinion of James remained high, even through the bitter days after James’ disappearance into the unknown. I think Selous saw in James the likeness of his own brother Edmund, saw a similar love for precise observations on the intricacies of nature. Selous and I shared the knowledge of a brother devoted to a meticulous labor.

Selous himself was a skilled observer not only of the game on which he depended, but also a student of both fauna and societies. He became fluent in native dialects, also understanding the Latin in a naturalist’s description. Though I did not share the naturalist’s bent with James, we were close in our quest for the next unknown. We shared an impulsive yearning for the undiscovered.

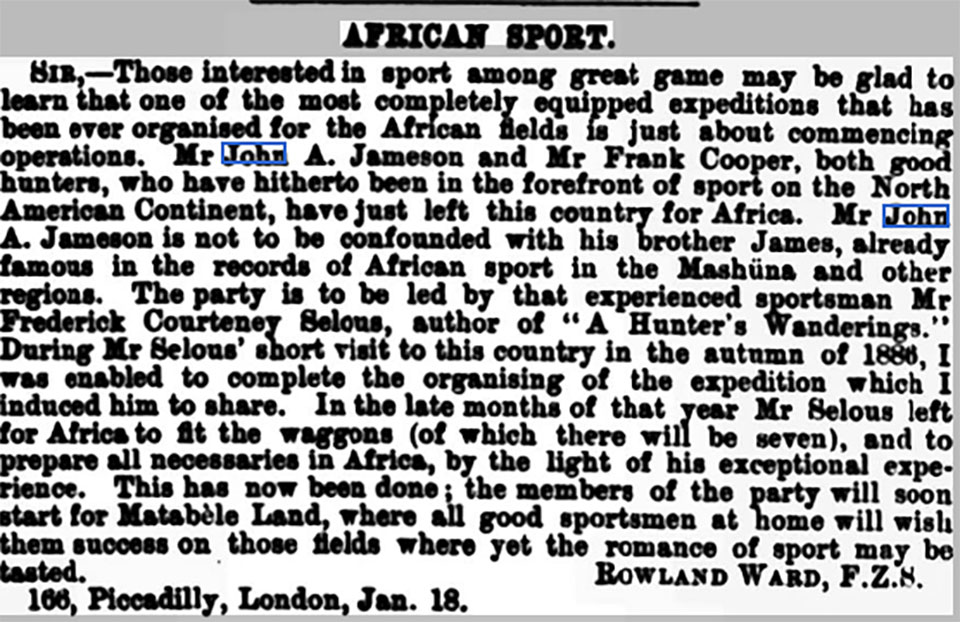

On one of Selous’ rare turns home James introduced me to Selous in this room. Dinner conversation with Selous convinced me to join him on an extended trek through uplands far north of the Limpopo River. We spent several weeks planning, as The Field of January ’87 stated, ‘one of the most completely equipped expeditions that has been ever organized for the African fields’” (The Field 01/22/1887, p 41.)

“It was certainly complete; food, clothing, transport, medicine, rifles, all the items necessary for months of trekking into a bewildering interior, hunting and trading. We spent days visiting the shops, selecting, planning, organizing. When Selous returned to Africa he collected wagons and oxen, porters and trackers. I shipped the kit we had gathered in London, then followed in January, ’87 and so we began.

With ox and wagon we trekked in towards Lobengula’s Bulawayu, did not return for over a year and brought out a respectable collection of heads, hides, and horns from the game of the interior. We had also a good lot of trade ivory. We sent the trophies to Rowland Ward for preservation, gave them to the Kensington, sold the ivory at a nice profit. We also brought out of that unforgiving interior the soul of our evening conversations.

“Crossing a Mountain Stream” watercolor by Charles Bell.

Phillida Brooke et. al., The Life and Work of Charles Bell.

Vlaeberg, S. Africa: Fernwood Press, 1998, p. 63

Even as I trekked with Selous, James joined Stanley’s expedition to rescue the Emin Pasha and the remnant of Gordon’s force. I was a bit wary of Stanley’s boasts, shared my apprehensions with James. My attempts to discourage him did not receive a hearing. James could see only an extraordinary opportunity, a chance to describe rare species of that river basin, possibilities for display, publication, and response from the Academy. He was thoroughly persuaded by Stanley’s rhetoric.

He trusted Stanley’s past success in the African wilderness. I could not alter those images. He sailed with Stanley. James and I were completely separated for that year and more, all our correspondence lost in the ambiguity of the interior. But then, you see, it was that insistent uncertainty within the interior which had always drawn James and me, forced us to live with the uncertainty much as a dream pulls one to unforeseen conclusions. On trek we did not think of distant endings and returns, only of the village or the water we could reach in the next days’ travel. We were intensely concerned with the future of each morning and perhaps its’ morrow.

My trek with Selous ended well. James’ trek with Stanley ended in a fever infested fog. In late spring, ’88, as I returned to London and marriage, James lay dying at a remote station on that ominous river, leaving his widow to suffer with his diary, his collections, and his disturbing legacy.

The extent of the Stanley disaster, the fate of his relief column on the Congo, reached a curious public within the year. His widow and I felt the full force of Stanley’s criticisms pointed sharply at his staff, and a public’s righteous disapproval of James’ curiosity touching on native customs. But they knew nothing of uncertainties within the interior, of being shut away from the familiar with its comforts, of being surrounded by an immensity of wilderness having not a touch of concern for the traveler, of meeting a new people with intriguing customs and strange dialect on every stretch of a far tramp into the uncharted.

James and I knew uncertainty at other points on the compass. We had lived with that bewildering aspect, felt the full force of its mysterious core luring us into a seamless horizon between fact and mystery far beyond our civil reason. We were hypnotized by the unknown. We went to Africa, each to a separate land, both to the very center of the interior’s mystery. I returned. James did not escape the mystery, his last days spent in that final uncertainty.

During our long trek I heard nothing from my brother, but learned the African meaning of “trek,” its plodding energy and persistent frustrations. It was hard work in an overwhelming wilderness. We lived as ‘itinerants,’ passing through areas held by the force of native muscle and spear.

When we reached the broad district held by Lobengula, the high plateau of Mashonaland, Selous gained the strong man’s permission to trek across vast stretches of that high savannah. We traded and hunted north as far as the Zambezi River, then from the falls of the Zambesi east and north. We shot hippopotamus in deep pools along its tributaries, giving the meat in trade to isolated hamlets.

In turn we enjoyed the gratitude, the goods, and the social life of those nameless villages. Selous was fluent in their dialects. I managed only a slight introduction to the Shona language. When stopped for protracted trade, we hunted out from fixed camps. As we hunted Selous learned the land, ranging from murderous desert to alpine chill. All this Selous faithfully noted in his daily log of the trek. His knowledge would later prove valuable in the ambitions of a Trading Company not long after the trek had ended.

I came for the hunt, but unexpectedly received much more than trophies. I watched as Selous played the roles of trader, hunter, diplomat, surveyor, switching from one to the other without a second’s hesitation, always gaining his ends. Selous’ genius was able to clarify ambiguities of the people and the land. We were drawn into regions I could not have imagined, ever sensing a firm closing of the track behind our march, the opening of the next reach with its intriguing discoveries.

We were well equipped for the hunt, both in experience and kit. As our hunts developed we became confident in each other’s skill, began conducting a dangerous experiment. By constant exposure to the tenacity of African game Selous developed a knowledge of rifle performance in the many situations of the hunt and began thinking in terms of smaller calibers for all game.

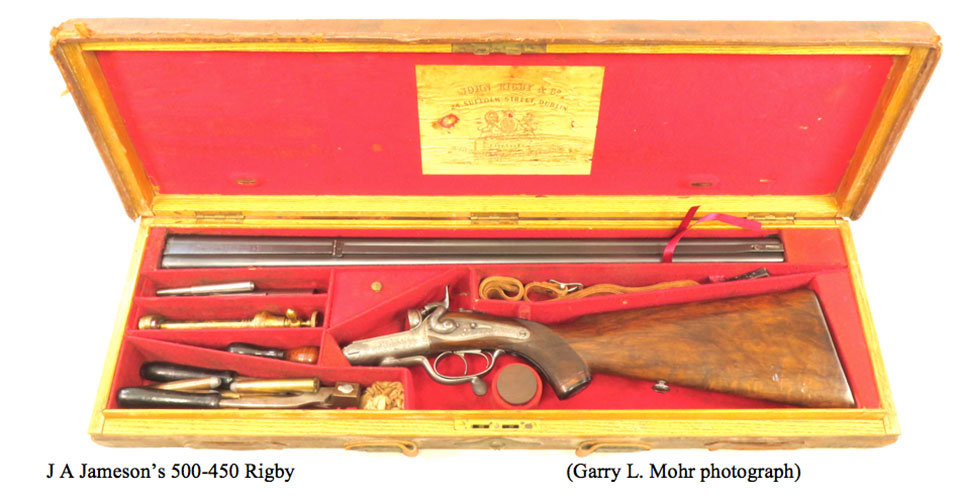

Selous owned a heavy rifle, a 10 bore, but rarely used it, preferring instead his lighter Gibbs 450 and a heavy hardened bullet over a case filled with powder. I had bought an 8 bore Purdey for larger game, but soon preferred my express Rigby 500-450 double.

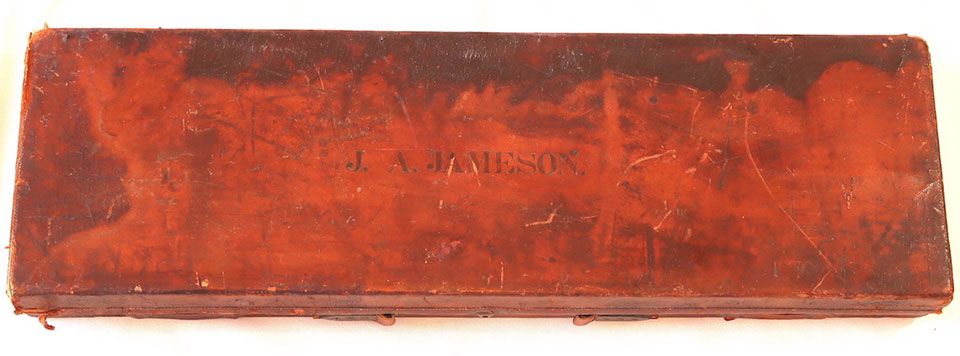

J. A. Jameson’s Rigby 500-450 (Garry L. Mohr photograph)

At nine pounds the Rigby was easy to carry when stalking and imposed less burden on my horse. While Selous’ rifle took the 450 case, my Rigby used the 500-450 case. We could not exchange cartridges. We took the tools needed to load our expended shells and a good amount of lead and powder. We had all that was needed to keep our cartridge belts full, enabling us to eat and trade by our rifles and, at a pinch, found powder and lead useful for barter.

I was impressed with my Rigby. The shop in Dublin built it to my specifications and measurements, with the addition of a collapsible “peep” sight mounted on the breech tang, a clever idea from James and valuable for distant game. At nine pounds it balanced just ahead of the hinge pin, the triggers properly adjusted for consistent pull, front trigger checked, the stock carved to fit my shooting.

With a subtle marbling in the stock, the entire rifle spoke of restrained excellence. I had it for tiger in India and, of course, took it on my trek with Selous. It was with me each day, fully acquitting itself on many hunts for game of the veld and, at times, for the dangerous ones.

Our trek passed through all seasons till we finally returned through Bulawayo. It was a profitable return, Selous made significant financial gain and I collected an impressive bag of trophies for display. We anticipated a pleasant impact from our venture on family, friends, and perhaps even a bit of the public eye. I took passage by homeward mail to London, intent on marriage and quiet time at Glen Lodge, County Sligo, eager to see James and his family.

Selous’ return could not have the pathos I would feel, yet it did have its own sorrow. As we spoke during that trek I could see in his intimations a passage from one life to another. He did not specify, yet there was, in certain comments, an indication that Selous dimly saw, as through a haze, closings of an old life, lacking direction into the next moment.

He detected increasing government interest in the Matabele country, perhaps gave it some sanction in a descriptive letter to certain statesmen interested in South Africa. Even as his comments appeared in the Times I believe he knew his depictions of the land would bring an end to free wilderness and his trekking life.

I returned to the insinuations of my acquaintances, vicious remarks in the papers, and intense public disdain for James’ role in the Stanley expedition. In the following years my mind was occupied with my brother’s hopeless days at the interior stations on that river in the center of Africa. I felt bitter remorse for not speaking more sharply to James on Stanley’s folly before it was committed. Explanation of his last days was impossible. Through his diary I heard James lament those monotonous days in the grip of a savage river, but was forbidden the chance to hear his last words.

His widow made a courageous attempt through the publication of James’ diary, but could not secure an understanding reader among a public maddened by sensation. I could not even voice a response, the magnitude of my grief was as great as the dimensions of the wilderness into which James and I had been drawn.

James had not returned. I was not permitted a return. Selous may have had indications of the coming change. I had not. It struck like a shot, paralyzing in its sudden heavy blow.

Though I would never again trek in Africa, I did not turn away from the aspect of wilderness. I sought its remnant in rivers near home. Away from the public eye, a fly rod in hand with its rhythmic movement brought some relief, if only because it forced me to concentrate on a single motion from one moment to the next. Watching the fly settle on a ripple, then move instinctively with the current engendered a return to that life with Selous, moving on the thin surface of the wild.

Seeing the strike affirmed the distant remove of nature from the painfully civil nature of the world to which I returned, in which I was hopelessly caught. I spent years alone by a river, watching that fly, waiting for every rise from the hidden depth.

While the Rigby saw extensive service on the trek I could not bear to lift it after my return to the news of James’ death. Only after the newspapers had quieted, years had passed, and I had slight ease from my sorrow, only then could I take up the Rigby again. I have been able to secure a lease for Lord Atholl’s preserve and lodge at Dalnamein in Perthshire.

The lodge is far from the whispering crowd, the highlands reminiscent of a high savanna in other lands. In a sense these days at Dalnamein now provide a measure of solace for those desperate years following my return. Sharp images from the trek with Selous enter my thoughts on these days at Dalnamein providing a measure of comfort.

All this time I received indications of the change imposed on Selous, his correspondence with Rhodes and The Times on the benefits of Mashonaland for the colonist, his guiding the small forces intent on opening those benefits. All this Selous could do better than anyone in Southeast Africa, but those journeys were not the trek Selous had lived. In a sense, those officious journeys placed a melancholy end on the trek. I knew of his return to London, his marriage and attempts at life near this city, then his returns to Mashonaland, the Matabeli troubles, and a farm.

Later I learned of his role in the inception of the Shikar Club, its attempt to preserve something of the time of shikar and trek before government meddling. I was pleased to see him here tonight. He organized the group, had met with them on other evenings. I wanted to hear him voice his thoughts on changes he had seen since our trek. I wanted to speak with him about our brothers and their fate, I needed to hear his wisdom. That has not happened tonight, our moment of conversation was all too brief for that sort of reflection. I fear I may never see him again. That thought is almost as unbearable as never hearing James’ final words.”

When JA did not continue, we could not comment. Some time passed, each of us vainly striving to find an acceptable end to the story. There could be none on a tale lost among incomprehensible uncertainties. With a jolt JA spoke, bringing us back to his presence, “I have bored you enough with an inconclusive story and suspect you now find me a bit tiring. I can only leave you with one other impression. I still have the Rigby. Though all else may go to the auction block, I will not part with the Rigby.

We are both scarred from hard usage in the hunt and senseless handling by the public. Avoiding all the “to do” and public face of the fall hunt, Rigby in hand, I still seek wilderness solitude on a bit of Highland moor in pursuit of larger game. I do not go on a trained shooting horse, but by foot, the horse only employed as transport for the game. A bit of a demotion you say? Yes, but I am happy for a brief glimpse into that small bit of the uncertainty.”

Night was complete when J.A finished his story, so complete we could not see another’s face. As we all knew much of the colonial politics of the day and the darkness over Europe, we knew there would not be another trek.

NOTES:

Sources: The basic facts concerning the lives of John Aloe Jameson, James Sligo Jameson and Frederick Courteney Selous are described in the following source materials. JA’s tale to his friends is, of course, not verbatim, but the point of the tale may not be far off the mark and does provide a considered perspective on the tragedy involving the Jameson brothers.

Records of Rigby Rifles ordered by John Aloe Jameson and James Sligo Jameson

were retrieved from Rigby Day Books by Diggory Hadoke, Rigby Archivist and Steve Helesley, student of Rigby history. Many thanks for their careful and thorough work.

Public record of John Aloe Jameson hunting in Montana and Wyoming may be found in:

Helena Weekly Herald, June 10, 1875, p 7.

Helena Weekly Herald, June 26, 1877, p 7.

Helena Weekly Herald, June 12, 1879, p 7.

Rocky Mountain Husbandman, Sept23, 1880, p 3.

Helena Weekly Herald, Nov 11, 1880, p 8.

The River Press, Apr 27, 1881, p 9.

Helena Weekly Herald, July 7, 1881, p 7; July 14, 1881, p 8.

The New North-west, Nov 4, 1881, p 3.

The Field, Dec 17, 1881, p 17.

Public record of John Aloe Jameson and James Sligo Jameson hunting in Montana may be found in:

Helena Weekly Herald, July 20, 1882, p 7.

Helena Weekly Herald, Oct 26, 1882, p 8.

Billings Herald, Apr 28, 1883, p 3.

Daily Enterprise, July 14, 1883, p 1.

The New Northwest, Nov 2, 1883, p 2.

The Field, Nov 17, 1883, p 25.

Frederick Courteney Selous’ reflections on his 1880-’81 trek with James Sligo Jameson were drawn from his memory and his “game bag journal” for that trek. These reflections may be found in his A Hunters’ Wanderings in Africa, Mac Millan Company, 1907, latest edition 2019, pp 295-323, in his Travel & Adventure in South-East Africa, Piccadilly: Rowland Ward and Co., Limited; 1893, pp. 441-446, 461-476, and in his African Nature Notes and Reminiscences, Long Road Classics, pp 119, 145, 242, 292-293.

Frederick Courteney Selous’ reflections on his 1887-88 trek with John Aloe Jameson were drawn from his memory and his “game bag journal” for that trek.

These reflections may be found in his Travel and Adventures in South-East Africa, Piccadilly: Rowland Ward and Co., Limited; 1893, pp159, 195-208, 437 and in his African Nature Notes and Reminiscences, Long Road Classics, pp 119, 145, 242, 292-293.

A brief note on James Sligo Jameson hunting and conducting ornithological studies in Borneo may be found in an appendix by B. Bowdler Sharpe (British Museum) in Jameson’s diary, Story of the Relief Column of the Emin Pasha Expedition. London, R. H. Porter, 1890, p.393.

The first hand source for James S. Jameson’s role in H. Morton Stanley’s expedition to rescue the Emin Pasha is found in: Mrs. James S. Jameson, ed., Story of the Relief Column of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition by the late James S. Jameson, Naturalist to the Expedition. London: R. H. Porter, 1890.

Public record of John Aloe Jameson’s trek with Selous in 1887-’88 may be found

in:

The Field, Jan 22, 1887, p 41.

Bucks Herald, Dec 17, 1887, p 5.

Army and Navy Gazette, Mar 17, 1888, p 9.

Morning Post, Aug 17, 1888, p 5.

Public record of James Sligo Jameson with Stanley in the Congo may be found

in:

Fife Herald, Sept 19, 1888, p 3.

Western Daily Press, Sept 22, 1888, p 3.

Irish Times, Sept 22, 1888, p 5.

St James Gazette, Sept 22, 1888, p 10.

The Field, Dec 22 1888, p 42.

Echo (London), Sept 22, 1888, p 4.

Civil and Military Gazette, Oct 19,1888, p 5.

Echo (London), Nov 26, 1888, p 2.

Public record of public response to J. S. Jameson’s role in the Stanley

Expedition may be fund in:

Dundee Advertiser, Jan 18, 1889, p 9.

Northern Whig, Nov 10, 1890, p 3.

Western Ties Nov 10, 1890, p 3

Public records concerning John Aloe Jameson are absent from 1890 till 1899. From 1899 till 1910 public records show Jameson fishing in Ireland and hunting in northern Scotland:

The Field, Feb 25, 1899, p 44; Aug 12, 1899, May 13, 1899.

Cork Daily Herald, Mar 30, 1900, p 7.

The Field, Feb 23, 1901, p 40; Apr 13, 1901.

Highland News, July 12, 1902.

Inverness Courier , Aug 7, 1903, p 3.

Northern Chronicle and General Advertiser for the North of Scotland,

Aug 10, 1904, p.6.

Public record of the Shikar Club:

The Field, June 11, 1910.

West London Observer, July 12, 1935, p 9.

Published by Vintage Guns Ltd on