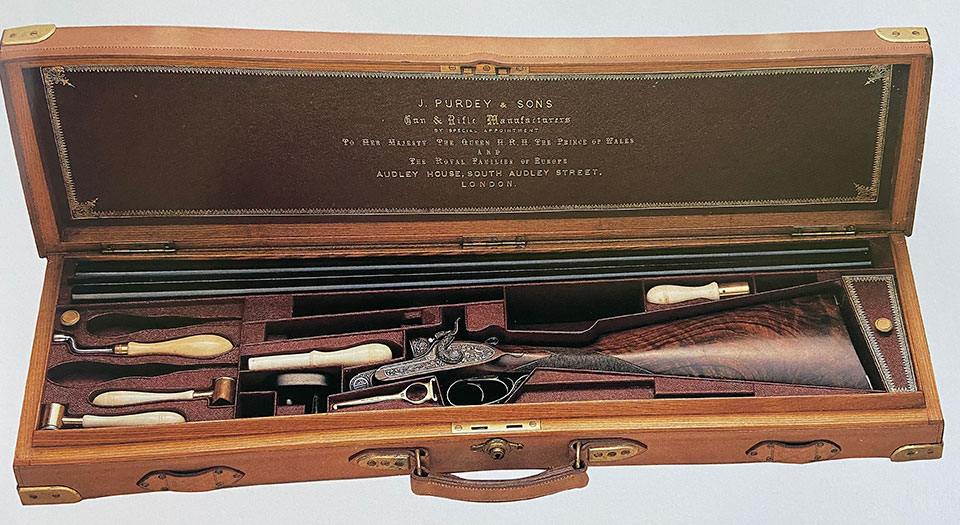

The highlights of Purdey’s stand at the Paris Exhibition of 1878 were undoubtedly the eight guns singled out in George Sala’s description of the display:

The extra Purdey exhibit consists of four guns, elaborately chased in the champ-levé style, two of which have been embellished by the talented artist Aristido Barri, who was arrested at Vienna as a Communist, but was subsequently released, and is now occupied in executing a champ-levé for the Emperor of Austria.

There is likewise a pair of very handsome guns, with stocks of ornamental maple, having the appearance of tortoiseshell, and the steel portions of which are exquisitely inlaid in gold. A pair of beautiful guns for ladies’ use must also claim a word. The stocks of these guns are ebonised, and the weapons themselves are of extreme lightness…

Purdey’s records are often frustratingly silent when it comes to the names of the engravers...

These were as much art works as they were sporting guns, and the epitome of what these expositions sought to display. Although such guns were extremely uncommon, Purdey’s records are often frustratingly silent when it comes to the names of the engravers responsible for such embellishment. The company’s 1885 catalogue suggested that this was because their clients primarily chose Purdey guns for their effectiveness in the field, rather than their ornamentation:

Best guns are made throughout on the premises by the most skilful workmen, and are distinguished by the perfection of balance, shape, finish, and shooting power, for which they have obtained world-wide celebrity.

This meant that the baseline for such guns was ‘Best’ quality, and that anything above this was described as either ‘Extra Quality’ or ‘Extra Finish’. These two terms were apparently interchangeable, and appear to have been used primarily to describe the stock selection:

If an especially selected handsome stock and extra finish are required they can be had in Best Guns on payment of £3 10s extra and such Guns are marked “Extra Quality”.

The fixed cost suggests that such guns only had ‘fancier’ wood, rather than special engraving. As the price of an uncased Best hammer gun at this time was £62, it shows the relatively small increase that ‘Extra Quality’ wood made in the overall cost of the gun.

Then as now, the cost of ‘Extra’ ornamentation, particularly at the level that was exhibited in Paris, formed a significant investment. The same catalogue included the following note about such guns:

WEAPONS SUITABLE FOR PRESENTATION, A SPECIALITY.

Guns and Rifles, chased in Champ-levé style, are works of the highest art, and are most suitable for presentation, being quite unique.

In the best quality only. Extra cost of chasing, from £40 to £50 per Gun or Rifle. Photographs on application.

Guns and Rifles inlaid with gold, with ebonised or maple stocks. Particulars with prices on application.

As can be seen, such engraving could cost almost as much as the gun itself. To have so many examples in one place, as Purdey did in Paris, was a serious investment for the company. It also means that it is relatively simple to identify the eight guns in Sala’s description on the shipping list, and their prices:

The four champ-levé guns:

No. 9563 – 12-bore bar-in-wood sidelock hammer gun (£94 10s);

No. 9568 - .450 (BPE) hammer double rifle (£120);

Nos. 10,140/1 –20-bore island backlock hammer guns (£210).

The gold-inlaid pair with maple stocks:

Nos. 10,110/1 –16-bore bar-in-wood sidelock hammer guns (£200).

The pair of Ladies’ guns with ebonised stocks:

Nos. 10,103/4 –28-bore bar-in-wood sidelock hammer guns (£140).

All four of the champ-levé guns have been attributed to Aristide Barré at various times over the last century, who was Purdey’s most famous engraver of such work in this period. However, there is no record that confirms this definitively, and if Sala was correct that only two were Barré’s work, the question is then which two?

entries for all four guns come at a period when Purdey’s record keeping was changing,

The Dimension Book entries for all four guns come at a period when Purdey’s record keeping was changing, and the initials of the men who had worked on a gun were still recorded alongside the serial number. The entries for Nos. 9563 and 9568 both have an ‘L’ in the column for engraving, which is believed to refer to James Lucas, Purdey’s head in-house engraver and responsible for creating the firm’s house engraving pattern. By contrast, the entries for Nos. 10,140/1 are blank, which is believed to indicate that the work was not done in-house. Therefore, it seems most likely that Barré only engraved Nos. 10,140/1.

Purdey guns engraved by Aristide Barré are extremely rare – just twenty-eight are definitively attributed to him, executed between 1884 and 1914, the year before his death. Although we can add to this two of the Paris guns, it is very rare to be able to do so. The only two direct references to Aristide Barré in Purdey’s records at that time both appear in the accounts ledgers.

The first, in the main accounts under “James Purdey” (apparently the Younger), is dated 31 December 1877 and records the payment of £10 14s to ‘A. Barré’. Sadly, there is no record of what this was for. The second is in the Private accounts of James Purdey the Younger, which includes the following entry under the “Contra” section against “Trade Charges”:

1878, April 17: By A. Barré, posted to Trade Exp. In P.C. by error - £1

There is also a reference to paying 16 shillings in duty on ‘Barre’s Cup’ in March 1883, but whether this also relates to the engraver is not clear.

In terms of the guns he is known to have worked on, they cover a variety of subjects, and all were chased. Where the design included a combination of both chasing and engraving, a second name is normally listed alongside Barré’s and is assumed to have carried out the engraving work. This suggests that Barré was only used by Purdey for champ-levé commissions, and not as a general engraver.

Given the much higher price of such guns, it is impressive that six of the eight had been sold by the middle of 1879. Nos. 10140/1 were sold to Dr Peter Yeames Gowlland in May 1879 for £210, but for many years they were the subject of some confusion, as the numbers are recorded in the main Dimension Book against two much plainer, individual guns. Gowlland died in 1896, but they do not appear to have resurfaced for sale until after World War Two, when they were offered at auction in 1947. It was not until Malcolm Lyell purchased them in 1956 and inquired about their history that the records were corrected.

The two remaining pairs were both sold to Timothy Hutchinson of Egglestone Hall, who was a prolific buyer of Purdeys in this period. Nos. 10,103/4 had a fairly convoluted sales history over the next decade. They were sold to Hutchinson in December 1878 for £148 8s, but returned in October 1879 for a credit of £83 8s. They were then resold to G.W. Brown in December 1880 for £136 10s, but returned again in August 1884 for a credit of £70. They then remained in stock until 1889, when they were split and sold separately for a combined total of £52.

these guns are still considered to be some of the finest examples of Purdey guns as works of art

Allowing for the various credits made, Purdey made a gross sale total of £183 10s across the four buyers. Nos. 10,110/1 has a simpler history, as they were sold in June 1879 for £220, and only returned on 30 March 1887, when Hutchinson was credited £120. They do not appear in his invoices between those two dates, suggesting they had not seen a great amount of use. They were resold two months later to Baron Keane for £150, who kept them until his death in 1901.

Keane is also connected to the two remaining guns, Nos. 9563 and 9568. They were the only two guns known to be exhibited twice, travelling to Sydney for a trade exhibition in 1879, priced at £100 (nett £90) and £125 (nett £112 10s) respectively. They may also have gone onto Melbourne in 1880, but no list for that exhibition survives.

Both were eventually sold to Keane, but at different times and possibly without his knowing they had been prize-winning guns. He purchased No. 9568 first, in July 1884 for £110, followed by No. 9563 in December 1885 for £93 4s 6d. Given their relative age, and the distances they had travelled, he received remarkably little discount from the prices they first had in 1878.

One hundred and forty-three years after the exhibition, these guns are still considered to be some of the finest examples of Purdey guns as works of art. Their rarity means that they have always had something of a collector’s following, and therefore are generally a source of interest when they do reappear on the market. Of the eight guns described by Sala, only Nos. 10,103 and 10,104 have not been seen since 1889.

Of the remaining six, three are currently believed to be in the hands of private American collectors, with No. 9568 featuring in a Shooting Sportsmen article in 2004. The other three (Nos. 9563 and 10,110/1) are currently displayed in the Royal Gunroom at Sandringham, having been left to the Royal Family by Keane after his death in 1901. The story of that bequest is the subject of my next article.

Author: Dr. Nicholas Harlow is Gunroom Manager at James Purdey & Sons, London.

Published by Vintage Guns Ltd on