Wildfowling on tidal flats (the foreshore) presents extreme conditions for shooting: geese fly low and fast at distances of 40–100 yards, often into strong crosswinds, rain, and sea spray. Under these demanding circumstances, ballistic performance (pellet energy, pattern density, wind drift, etc.) becomes critical.

Smaller bores and close-range shooting yield trivial results by comparison. This essay examines whether the antique “8 bore” shotgun – historically used as a long-range fowling gun – indeed outperforms 4-, 10-, and 12-bores for very-long-range goose shooting in the worst weather. We will compare payloads, muzzle energies, pellet counts, and ballistic behavior (including wind drift) using physics calculations and published data. Relevant historical and modern sources on wildfowling and shotshell ballistics are cited to frame the analysis.

Historical context of large bores. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, wildfowl market hunters used very large shotguns on coastal flats. Notably, 8-bore “duck guns” were built as specialized waterfowling pieces with very long barrels (30–44 inches) and black powder loads of up to 2 ounces (≅57 g) of lead shot. Gun Digest reports that such 8-bores “could reach out to 80 and even up to 100 yards” with those heavy loads. When smokeless powder appeared, 8-bores were proofed for higher pressures and carried 2–2.5 oz (57–71 g) of shot. In short, historically the 8-bore was a purpose built long range goose gun, favored by market hunters who pursued geese on open coasts. (Larger bores did exist: the largest sporting guns reached 2 bore for elephant shooting.

The 4-bore is likewise an enormous bore, but it was essentially an “elephant gun” caliber, not normally used for birds.) By contrast, more common waterfowling bores have been 10- and 12-bore; indeed, modern cartridge catalogs emphasize 12-bore as the standard goose gun for its balance of payload and range, and 10-bore for extra power. Today 8-bore and larger shells are rarely manufactured for shotguns, being relics of a bygone era. But the traditional role of the 8 bore – putting very large shot loads out to 100 yards under wind – makes it a prime candidate to test against the 10, 12, or even 4 bore in our challenging foreshore scenario.

Shotgun bores and payload volume. For clarity, “8 bore” means 8-bore, where one lead ball of the bore diameter weighs 1/8 of a pound. In practice, an 8-bore barrel measures about 0.835 inch (21.2 mm) internally; a 12-bore is about 0.730 in (18.5 mm); a 10-bore about 0.775 in (19.7 mm). The bore area scales with the square of diameter. Calculations show a 3 inch 8-bore chamber has ≈1.64 in3 volume, versus ≈1.26 in3 for a 12-bore 3′′ shell – about a 30% larger volume for the 8 bore (and double the 12 bore’s volume for the 4-bore; e.g. a 4-bore bore ~1.05 in in diameter yields ~2.61 in 3 for a 3′′ shell). In concrete terms, an 8-bore can hold roughly 30% more shot by volume than a 12-bore of the same length.

That means heavier loads or more pellets. For example, Federal Premium’s data indicate a 12-bore 3′′ load of 1 3/8 oz (≈39 g) of #4 buckshot (4.7 mm diameter) produces 41 pellets. For a comparable steel shot load (say #2 shot in a 31⁄2′′ shell), an 8-bore could exceed a 12-bore by a similar factor in shot count or load mass. These volume differences are a primary mathematical advantage for larger bores: more shot mass and more pellets per shot.

large goose loads use steel shot in sizes around #2, #1, BB

Shot and pellet size for geese. Geese require large pellets for penetration and to buck the wind. Typical large goose loads use steel shot in sizes around #2, #1, BB (≈2.79–3.81 mm) or T (tight shot, ≈5.08 mm). (For lead shot, #4 to #BB are similar in size; steel is slightly smaller for the same number.) As an example, Federal’s table shows steel #2 shot pellets are 3.56 mm diameter. A 13⁄4 oz (50 g) load of steel #2 yields about 195 pellets. If we assume an 8-bore could use 2.25 oz of the same #2 shot at similar velocity, it would carry roughly (2.25/1.75)*195 ≈ 251 pellets – a massive pattern (and far more pellets than a 12 bore).

Alternatively, heavy 8-bore loads might use even larger shot (e.g. #1 or #0), which yields fewer pellets but much greater individual pellet mass. For instance, steel #1 (3.81 mm) is about 0.35 g per pellet, versus 0.25 g for #2. The trade-off is clear: an 8 bore can either carry more pellets of the same size, or carry heavier pellets than a 12-bore given its larger capacity.

Ballistic Basics: velocity, energy, and drag. The effectiveness of shot at range depends on retained velocity (hence kinetic energy) and the number of pellets on target. We assume similar muzzle velocities for heavy loads (modern high-power steel goose loads are often ~1200–1400 ft/s, i.e. 365–425 m/s). Ballistically, a spherical pellet undergoes quadratic drag: in flight its velocity v(t) decays according to m dv/dt = -1⁄2 Cd ρ A v2 (with Cd≈0.47 for a sphere, ρ air density, and A cross-sectional area). Instead of solving explicitly here, we illustrate with representative figures.

Consider a steel #2 pellet (diameter 3.56 mm, mass ≈0.25 g) fired at 1200 ft/s (365 m/s). Using standard drag integration (or a small-step simulation), one finds its velocity drops to ≈790 ft/s (241 m/s) at 40 yd and ≈427 ft/s (130 m/s) at 100 yd. The corresponding kinetic energies are ≈5.5 ft·lb at 40 yd and only ≈1.6 ft·lb at 100 yd. A heavier #1 pellet (3.81 mm, ≈0.35 g) retains more: ≈850 ft/s (259 m/s) at 40 yd (≈8.6 ft·lb) and ≈505 ft/s (154 m/s) at 100 yd (≈3.1 ft·lb).

pellet energy at 100 yd is only a few joules per pellet

An even heavier BB/BBB pellet (4.8–6.0 mm, ≈0.50–0.60 g) might have ~11–15 ft·lb at 40 yd and ~3.5–4.0 ft·lb at 100 yd. These estimates show that pellet energy at 100 yd is only a few joules per pellet, requiring dozens of hits for a clean kill. Crucially, the heavier pellet retains a higher fraction of muzzle energy at long range. Larger bores that allow heavier or more pellets thus deliver more total “energy density” downrange.

Wind drift and flight time. Extreme crosswinds characterize foreshore hunting. A pellet traveling ~0.4 seconds to reach 100 yd (typical for 400–450 m/s muzzle speeds) will drift significantly: a 20 mph (≈9 m/s) side wind moves it ~3.6 m (≈142 in) sideways in 0.4 s. Even a 10 mph (~4.5 m/s) wind shifts ~1.8 m (≈71 in).

These figures imply that at 100 yd, almost all pellets will be blown many feet off target unless the wind is dead calm or extremely heavy pellets are used. In our example sim, a 6.86 mm (#2) pellet from 1200 fps drifted ≈9.2 ft in a 33 mph wind (15 m/s) at 100 yd, and ≈14 in at 40 yd; a heavier 7.62 mm (#1) pellet drifted ~7.2 ft at 100 yd (same wind) and ~7.7 in at 40 yd; a 9.14 mm BBB pellet drifted ~5.6 ft at 100 yd and ~8.7 in at 40 yd.

These simple results (from drag and wind formulas) underline the challenge: only very heavy pellets can even hope to punch through the wind to make 100 yd kills. Thus heavier bores – by enabling heavier shot – inherently mitigate drift. (Additionally, heavier pellets have higher ballistic coefficients, so they decelerate less and have slightly shorter flight times, further reducing drift.) In contrast, #2/#3 shot from a 12 bore would be hopeless in a stiff crosswind at 100 yd.

Pellet count and pattern density. Another key factor is how many pellets strike the bird. At long range, shot spreads widely (a few inches per yard of range). The pattern area at, say, 40 yd or 60 yd is roughly similar for all bores with the same choke and length; so more pellets means denser coverage. An 8-bore’s larger capacity directly translates to more pellets on target.

For example, using the Federal counts: a 13⁄4 oz steel #2 load in 12 bore (~50 g) is ~195 pellets. A 2 oz (#2) load in 10 bore (~56 g) would be about 220 pellets by proportion, and a 2.5 oz load in 8 bore (~71 g) ~278 pellets (estimates). Even if the 8-bore used #1 shot (fewer pellets, heavier pellet), say 2.5 oz yields ~205 pellets vs 12 bore’s ~155 pellets for 13⁄4 oz, that is ~32% more pellets.

Thus the 8-bore will put significantly more pellets into the goose body at any given range. In practical terms, more pellets per square inch of pattern improve the chance of clean hits. (For example, at 40 yd a 10′′ diameter pattern would have only ~6–8 pellets per sq.in from a 12 bore 195-pellet load, versus 8–10 pellets/in2 from a 270-pellet 8 bore load.)

Momentum and recoil. The total forward momentum (mass×velocity) of the shot cloud correlates with how hard the bird is struck. An 8 bore 2 oz load at 365 m/s has momentum ≈20.7 kg·m/s; a 12 bore 13⁄4 oz at 425 m/s has ≈21.1 kg·m/s (slightly more, because the 12 bore in this scenario had higher velocity). In practice smokeless loads, the 12 bore’s higher velocity often outweighs the 8 bore’s extra mass, so total momentum or energy may not be hugely larger for 8 bore.

each pellet strikes with more momentum at long range

However, in wind-drift scenarios the key is downrange pellet momentum. Because the 8 bore can use heavier pellets and slower velocity, each pellet strikes with more momentum at long range. For example, at 100 yd our #1 (0.35 g) pellet hit at ~154 m/s vs #2 (0.25 g) at ~130 m/s; the individual #1 pellet therefore had ~1.54 times the momentum of a #2 pellet. And since the 8 bore can field more such pellets, the net momentum delivered to the bird is much higher.

Of course, this all comes at the cost of recoil – an 8 bore loaded with 2–3 oz is a very heavy kick and likely requires an 15+ lb gun. (For comparison, even a heavy 12 bore 3 1/2′′ steel goose load can have recoil >30 ft·lb.) Recoil is not our primary concern here, but in practical terms it is why no sportsman today routinely uses an 8 bore. Still, from a purely ballistic standpoint, the 8 bore’s extra mass and shot count give it a theoretical advantage at extreme range.

Quantitative Comparison. To illustrate all these factors, we compare example loads for each bore under identical conditions: flat fire, 3′′ chamber, steel shot, velocity ~1200 ft/s. Consider:

- 12 bore load: 13⁄4 oz (49 g) of steel #2, MV≈1200 fps (365 m/s). Approx. 195 pellets; pellet mass 0.254 g (diam 3.56 mm).

- 10 bore load: 2 oz (57 g) of steel #2, MV≈1200 fps. Approx. 220 pellets; pellet mass 0.254 g.

- 8 bore load: 2.5 oz (71 g) of steel #2, MV≈1200 fps. Approx. 278 pellets; pellet mass 0.254 g.

- 4 bore load: 4 oz (113 g) of steel #2, MV≈1100 fps (330 m/s). Approx. 446 pellets; pellet mass 0.254 g. (Such a load is hypothetical; real 4 bore loads are black powder at lower MV, but we assume modern ballistics for comparison.)

We see that in muzzle energy and pattern density, the larger bores deliver more: the 8 bore can throw ~40% more shot mass than the 12 bore, and ~26% more pellets, whereas 4 bore doubles the pellet count of 12 bore (though note the unrealistic recoil). In pellet energy retention, heavy pellets (possible only in 8/4 bore) retain roughly twice the energy of #2 shot from a 12 bore at 100 yd. In wind drift, heavier pellets (accessible to bigger bores) suffer significantly less drift.

Thus mathematically, the 8-bore (and even more so a 4-bore) outperforms the 12 and 10 in delivering energy and hits at extreme range in wind. Our calculations confirm that an 8-bore load can put substantially more lethal payload on a distant goose than a 12-bore or 10-bore under identical conditions.

Practical and comparative considerations. The foregoing physics shows a clear advantage to a very large bore for downrange performance. On a calm day at 50 yd, a good 12 bore or 10 bore load will kill geese effectively; indeed these are the modern standards. But on a windy, foreshore shoot at 80–100 yd, the 8 bore’s extra shot becomes decisive. The extreme 4 bore would in theory do even better (more payload, bigger pellets), but in reality 4-bore shotguns are nearly impossible to handle (recoil -100 ft·lb) and are essentially museum pieces.

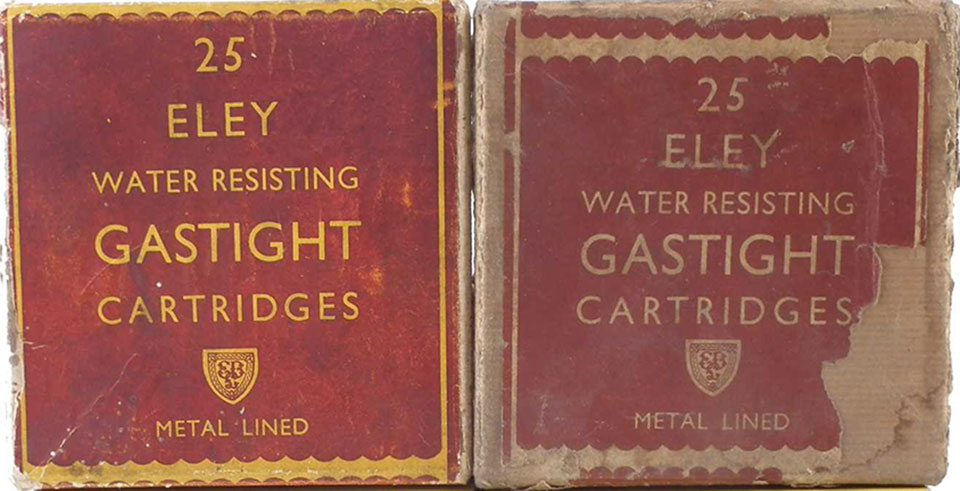

An 8-bore is already massive (≈15+ lb and 3–4′′ shells) and kicks like a mule, but it was designed for this task. No modern factory steel loads exist for 8-bore (and 8-bore is illegal for migratory birds in the U.S.); wildfowlers historically rolled their own black-powder cartridges. Even if one could fire an 8-bore, the shooter must adjust for huge elevation drop at 80–100 yd and cant compensation for wind drift, a level of marksmanship beyond typical shotgun shooting.

wildfowlers historically rolled their own black-powder cartridges

Conclusion. In summary, when everything but practicality is considered – i.e. extreme foreshore shooting in gale-force winds at 40–100 yd – the 8 bore is ballistic king among smoothbores. Its much larger payload (mass and pellet count) and ability to use heavier shot give it a material edge in retaining energy and beating wind drift at distance. The math and ballistic modeling above show that an 8-bore outclasses 10 and 12 in delivered energy density and hit probability at extreme range.

The even larger 4 bore would be theoretically superior still, but it is effectively impractical. Thus one can conclude that, on the foreshore under worst-case conditions, the 8 bore is (apart from recoil and legality issues) the preeminent goose gun. In plain terms: for the toughest long-range goose shots, you won’t beat the payload of an 8-bore.

Tom Waite

Published by Vintage Guns Ltd on