British gunmakers are household names in sporting circles; still revered and proudly discussed around many a log fire, over a dram and a cigar; though few shooting men walk afield with a Purdey, Rigby or Westley Richards, nowadays. A new one costs as much as a Range Rover; so it is not really surprising.

British gunmakers once furnished everybody with their guns, not just the elites; from the Prince of Wales, right down to the tenant farmer, the gamekeeper and even the local poacher! Indeed, anyone who set off in pursuit of fur or feather would once have done so with a gun made in London or Birmingham.

Looking at the wares of a generalist gunmaker from just before The Great War, we can see the range of British-made guns the average shooting man could buy in our great-grandfathers’ day.

For the 1912-13 season. W.J Jeffery sold a ‘best’ quality, ‘London Pattern’ side-lock ejector for £55. Then, the average salary was £70 per annum, though a skilled worker could earn £100. So, a ‘best’ gun represented half a year’s salary to the 1913 equivalent of today’s ‘Mondeo Man’.

In modern money that represents £19,000; a long way from the £100,000 cost of a new London side-lock but it was still more than most people spent on a shotgun. It still is. Jeffery also offered a ‘Farmer’s Gun’. This was an Anson & Deeley boxlock retailing at just five pounds, 10 shillings. That is Yildiz money to the modern buyer.

For the middle classes, Jeffery advertised; ‘a good gun at a low price’, which was also an Anson & Deeley action, with Southgate ejectors and nicely engraved; it retailed for 12 pounds, 12 shillings. This represents about £1,500 today.

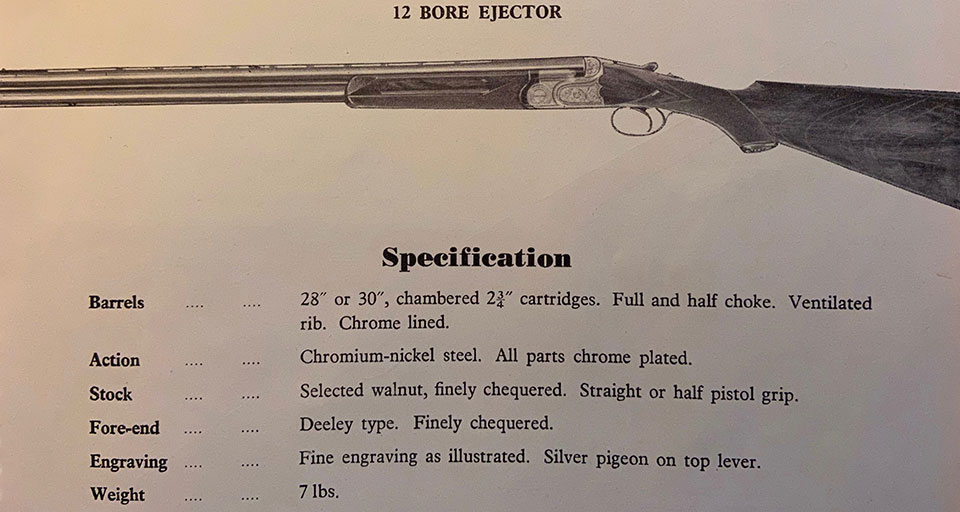

Moving forward in time, to the 1950s, Thomas Bland’s ‘best’ sidelock, similar to the one Jeffery was selling in 1913, had jumped from £55 to £280. Bland’s ‘Model B’ Anson & Deeley gun was similar to Jeffery’s ‘good boxlock’ and cost £82, while the ‘budget’ boxlock non-ejector was £68.

The 1955 ‘Mondeo’ equivalent; the Austin A50, cost £646. So, a good British boxlock cost an eighth of the price of a family saloon car, while the weekly wage of a manual worker was £9.25 and income tax was 47%. Today, a Ford Mondeo starts at just over £25,000 so the equivalent figure for a mid-range gun today would be £3,125, which is double what it had been forty years earlier. There was clearly an opportunity for foreign makers, with lower overheads and new designs, to try their hand in the British market.

The origins of Beretta’s sporting shotguns

Beretta may not have made much of an impression on the average British sportsman for most of its existence but the firm has been in the business of making guns for centuries. The founder was born in 1490 and by 1880 the company was building eight thousand guns a year.

The 20th century saw rapid expansion at Beretta. In the 1930s, The SO Model appeared as a quality side-lock with leaf springs and had a bolting system which allowed for a lower-profile action than the over & under design of J.M. Browning, with its conventional under-lumps.

It was a success, especially with clay target shooters, but it was still largely hand-made and expensive. The breakthrough was, perhaps, inspired by Beretta’s military arms facility, where everything had to be machine made and parts interchangeable.

The interchangeable concept was not new to the industry; Birmingham gunmakers had been trying to do it since the 1860s but it had never quite worked-out for sporting guns. Even Bonehill’s ‘Belmont Interchangeable’ boxlock (from about 1880) needed skilled fitting of replacement parts.

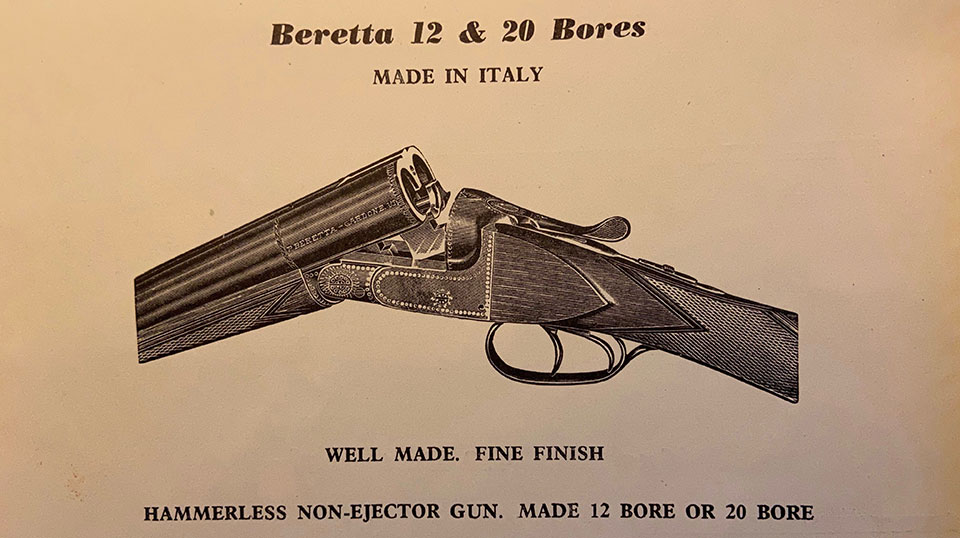

In the 1950s, Beretta introduced more machine production; enabling their guns to be produced faster and sold at a lower cost. Bland began importing Beretta over-and-under guns in the mid 1950s. They made increasing inroads, into the clay shooting scene in particular, through the 1960s but it was not until Gunmark became the UK agent, in the mid-1970s, that sales really took off.

Beretta arrives in Britain

During the late ‘50s and early ’60s, while British firms were selling mid-market, Birmingham boxlocks, Beretta was testing the market with its alternatives. A Beretta boxlock, at £57, was almost half the price of a Webley. The ‘under-and-over’ Beretta ASE cost £144, compared to a Boss over-and-under at £600. Of this, Beretta said; “In creating the first Italian over-and-under, we decided to manufacture a weapon really superior to any other on the market”.

When introduced, it was almost the same price as a Browning B2. However, it was still half the price of a ‘best’ provincial side-lock.

Browning led the way with mass-market over-and-unders with the ‘Superposed’; and was starting to pick-up customers in Britain by the 1960s. Brownings however, were expensive and complex. A Belgian-built B25 was, as Mike George wrote; ‘a Rolls Royce of a gun trying to compete in a growing Ford market’.

The Clay Factor

The popularity of clay shooting increased demand for modestly-priced over-and-unders. Clay shooters were often introduced to the sport with over-and-unders and, once hooked, were reluctant to give them up when the opportunity to shoot game arose. Though residual snobbery around over-and-unders on game shoots lingered into the 1980s, it gradually, then rapidly, disappeared.

Percy Stanbury won the British Open in 1953 with a Webley & Scott side-by-side weighing 7 1/2lb, with a high comb, semi-pistol grip and raised flat rib. These features rendered it handle more like an over-and-under than most side-by-sides, it may have been inadvertent but the message was there in wood and metal; over-and-unders were the future of competition shooting.

Yet, Stanbury’s 1962 book ‘Shotgun Marksmanship’ barely mentions over-and-unders. ‘They do have their devotees, more particularly for clay shooting’, he comments. L.B. Escritt, writing about trap shooting in ‘Rifle & Gun’ (1953) merely says ‘Over-and-under guns are particularly suitable’, but, despite pages about various types of side-by-side, the over-and-under is not discussed in any detail.

Despite the performative and aesthetic success of the SO, it was necessary for Beretta to design something more affordable to make and buy if they were to compete in the mass market. The answer was the 600 Series.

600 series guns have replaceable lateral stub-pins acting as the pivot, rather than conventional lumps, acting on a hinge pin, like a side-by-side (or a Browning). This modification reduces the action depth by around half an inch.

However, it also removes the possibility of bolting the gun shut with a sliding-bolt acting on bites in the lumps. Beretta is generally credited with the solution: two conical bolts, which emerge from the breech-face, to engage with matching recesses either side of the top barrel.

However, the concept originates with W&C Scott. Patent No.2052 of 1874 shows a side-by-side with a very similar arrangement, also operated by a top-lever. In Scott’s patent, these bolts acted in tandem with a sliding under-bolt, but Beretta uses them as the sole means of holding the barrels and action together.

Beretta 600 series guns are often, erroneously, referred to as ‘boxlocks’, while they are really trigger-plate actions with coil springs. Coil springs are easier and cheaper to make than the traditional leaf springs of a British side-lock or Anson & Deeley action.

Beretta also sold the SO series, the ASE series of competition guns (these had hand-detachable mechanisms) and the semi-automatic range, like the A300 and A301. However, of the four types in the production line, it was the 600 series that stole the show.

Early success was marred slightly by a few teething troubles; which are common to most new mechanical products. Early Model 682 guns were set-up for a 32 gram competition load and there were problems with misfires on the second barrel when lighter loads were used. They were also a little heavy and ‘clunkier’ than later ones. The 686 and 687 models were available configured for competition or field use and were good, reliable, attractive guns, priced right for a ready market.

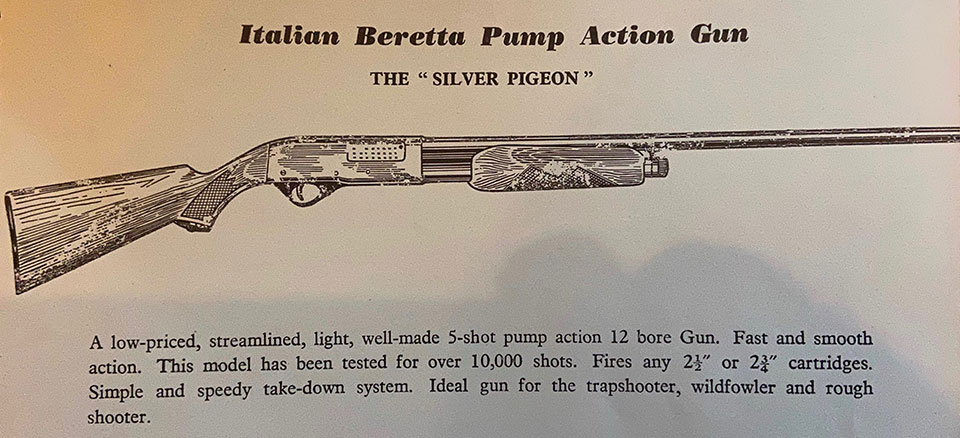

The name ‘Silver Pigeon’ was applied to the 686 and 687 in the 1990s but it has been part of Beretta’s vocabulary for a long time. The ASE model in British advertisements of the ‘50s had a silver pigeon on the top-lever. However, the first gun actually marketed as a ‘Silver Pigeon’ was a pump action!

Published by Vintage Guns Ltd on (modified )