It is tempting to look no further than London-pattern sidelocks and boxlocks with familiar actions and features. However, gunmakers have always been busy trying to make guns better and find a new concept they can sell to the public. We take a look at a few of those here.

Trigger Plate Actions

The trigger plate principle was applied early in the hammerless era – in fact the Murcott was available both as a trigger-plate or a sidelock action in 1871. The concept took the lock-work away from the plates fitted to the sides of the action and mounted everything on the trigger plate, where it could be inserted from the bottom of the action. This left the action bar very strong and the weight firmly between the hands.

The trigger plate side-by-side became something of a Scottish speciality through the work of Edinburgh gun makers John Dickson and James MacNaughton, (though Stephen Grant offered a version of his own) but they have also found favour in the modern era for application in over & under guns. Trigger plate actions are now widely employed by Beretta and Perazzi, among others, and as ‘best’ guns by David MacKay Brown.. A good example of the Victorian trigger plate action gun is the famous Dickson ‘round action’.

The Dickson ‘Round Action’ Hammerless Gun

Introduced in 1882

Type: Trigger Plate Action

Cocking System: Barrel-cocking

Bolting System: Purdey double bolt operated via top-lever & Scott spindle.

Dickson & Murray patented the ‘round action’ in 1882 and it was also used for three-barrel guns, of which Dickson, of Edinburgh, made a number of variants. However, the classic Dickson ‘round action’ is best known as an elegant side-by-side double.

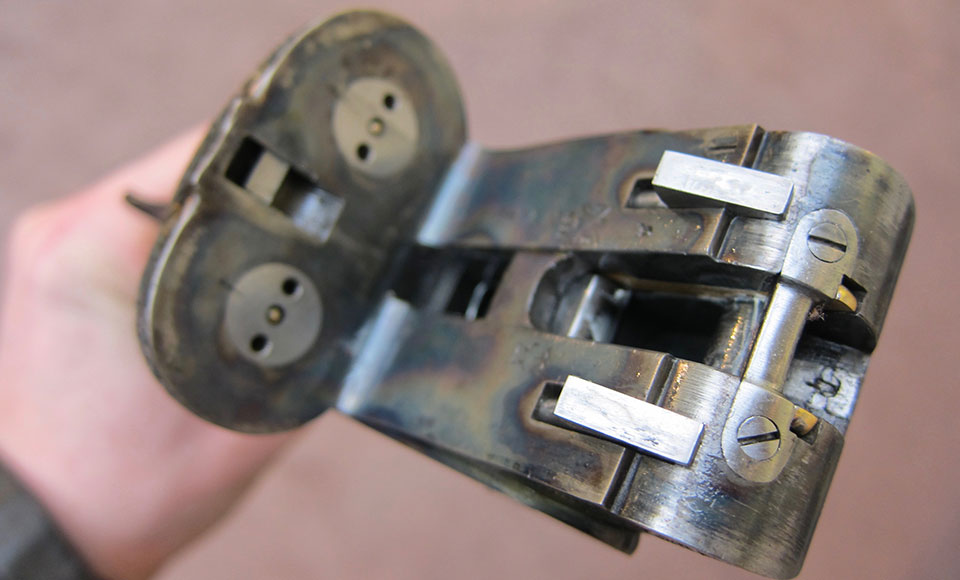

The Dickson lock-work is entirely mounted on the trigger-plate and can be removed in one piece from the underside of the action. It is cocked by the fall of the barrels and has as its great merit, strength of action-bar without weakening the hand of the stock. Subsequently, the Dickson can be made very light yet remain robust, with weight centred in the forward part of the action, around the hinge pin. This gives the guns great ‘liveliness’ and makes them very pleasant to shoot. The eminent critic Major Burrard lauded the inherent strength of the design and believed it in every way equal in merit to the finest bar-action sidelock. Its one failing in the Major’s eyes was the absence of an intercepting safety bolt or sear. Dickson’s will argue that a well-made gun does not need one.

The Dickson is a current production model; still offered by the Edinburgh firm and to date around 2000 guns have been made by Dickson using this action. It also forms the basis of the current guns of David MacKay Brown of Bothwell, near Glasgow.

Having perfected four basic types of hammerless gun (boxlock, trigger-plate, bar-lock and back-lock), all of which have proved their worth, one may be forgiven for thinking that the well of invention dried up after about 1890. However, this was not so. There were fads, fashions and improvements that were to lead to new designs and patents to met the consequent demand. A good example was the drive towards lighter game guns in the early part of the 20th Century. In this, the old firm of Charles Lancaster would again rise to the fore with the iconic ‘Twelve-Twenty”.

The Lancaster ‘Twelve Twenty’

Introduced in 1906 (1924 by Lancaster)

Type: Back-action sidelock.

Cocking system: Barrel-cocking.

Bolting System: Purdey double bolt operated via top-lever & Scott spindle.

The ‘Twelve Twenty’ reflected the fad for very light game guns in the early decades of the 20th Century and its design ethos echoes Greener’s musings of almost twenty years earlier, in which he advocated the merits of back-action locks for light game guns.

Brilliant Birmingham gunmaker William Baker patented this clever back-action design in 1906 with the intention of applying it to lightweight 12 bores of around 6lbs. In the stylistic conventions by then established, it retained the outward features of the Beesley/Purdey side-lock, with its graceful lock plates and stocking to the fences. The mainspring, however, was housed in a box in the backward extremity of the lock-plate.

The gun automatically cocks the tumblers when the barrels fall but the mainsprings are cocked when it is closed. It operates as an assisted-opener, with a separate cocking spring which rotates the tumblers and presses on the mainspring housing, having some of the ‘easy-opening’ effect of the Purdey/Beesley but not requiring quite as much effort to close. In common with the Purdey, the springs are always ‘at rest’ when the gun is disassembled.

The gun was extensively marketed by Charles Lancaster in the 1920s and 1930s (by then managed by HAA Thorn) as having all the handling qualities of a twenty-bore but retaining the ballistic advantage of the twelve and obviating the need to have more than one type of cartridge; the possibility of twenty-bore cartridges mixing with twelve-bore guns being notoriously risky.

The gun was a success, Major Burrard (who wrongly credits Lancaster with the invention) writes especially favourably about its lightness, strength and crispness of trigger-pull. Baker (and possibly others) subsequently made guns on this action for many well-known firms, including Stephen Grant, William Powell and Churchill, who all retailed it under various brand names. However, the Lancaster is the best known and most often quoted. Indeed, most laymen probably believe Lancaster to be the originator. In this respect, Baker, like Beesley before him, lost his place in posterity through selling his invention to a ‘bigger fish’, who took all the credit. Even modern writes commonly credit Lancaster with the ‘Twelve-Twenty’. Donald Dallas, writing on the gun in The Shooting Gazette in 2005 neglects to mention Baker at all in his historical and technical appraisal.

The Churchill XXV Concept

There is an argument that Robert Churchill’s championing of a light game giun with 25” barrels should be consigned to debate in the ‘barrel’ section of a book like this. However, Churchill’s concept was more than the mere reduction of barrel length in a normal gun. Therefore we shall consider the package as Churchill presented it to the shooting world in its entirety rather than simplify it to its base component.

There is no one action on which Churchill built his ‘XXV’ guns. He employed sidelocks like the 1906 Baker used in the Lancaster ‘Twelve Twenty’ and the Smith ‘pinless’ action but he also used a Smith boxlock, as well as other variants of the Anson & Deeley design.

Churchill contended that 25” was sufficient to burn all the nitro powder needed to propel the shot from a modern gun and that proper choking of such barrels would ensure patterns as tight as necessary. Ballistic tests over the years have proven Churchill correct. A 25” barrelled gun will perform as well as a 30” barrelled gun I terms of pattern and penetration. The shorter barrels reduce weight and make a gun that is faster to move and which lends itself to the ‘snap-shooting’ style that Churchill coached.

Churchill also produced a stock and balance profile that suited his gun, The ‘natural’ stock he advocated has a swept comb and a longer butt-sole than was then the norm. Consequently, the stock is ‘higher’ in profile than a normal game gun stock and more triangular. These features promote fast, regular mounting of the gun to the face with minimal head movement. He also developed a special raised, tapered rib to provide an illusion of length on the sight-plane.

Al kinds of legends and myths surround the ‘XXV’ concept and many dismiss it as an advertising gimmick. However, it was extremely influential and has split many ‘shooting authorities’ from 1914, when first mooted until the present day, when longer barrels are again in fashion.

Complications

A hammer gun is easy to open and close because there is no impediment to the fall or rise of the barrels or the operation of whatever lever is employed. With the introduction of hammerless guns, and with them automatic cocking, this ease of opening was sometimes compromised; the barrels or lever being used to cock the tumblers or compress the mainspring. As barrel cocking became favoured over lever-cocking, attempts were made to ensure that hammerless guns opened quickly and easily to ensure speed ease of loading. Some patents, like the Perkes back-action of 1878, reduced this ‘drag’ on the falling barrels by cocking one lock with the fall of the barrel and the other upon closing. However, such actions were over-complicated and although variously used by Holland & Holland, Boss and Cogswell & Harrison, the idea fell into disuse. Instead, makers started to consider how the mainspring, or a spring housed elsewhere, may be used to power the opening of the gun and assist the falling of the barrels.

Self-opening Mechanisms

Also jokingly referred to as ‘hard-closing’ mechanisms, the self-opener acts to force open the breech when the operating lever is moved to un-bolt the barrels from the action. There are a number of variants but the true self-opener works whether the gun has been fired or not, the mainspring typically being used to provide the power, acting on rods and ‘kickers’ that protrude through the action bar and act on the barrel flats to press the two apart. Probably the best-known self-opener is the 1880 patent of Frederick Beesley, since that time found employed as the action for all Purdey’s hammerless guns. A true self-opener employs both mainsprings to cause the gun to spring open, the springs being cocked by the barrels when the gun is closed. Holland & Holland took a different route entirely and when they made their ‘Royal’ self-opener it was powered by coil springs separately housed under the forend.

The late Gough Thomas noted certain advantages for the self-opening gun. Apart from being quicker to reload, Thomas suggests that they reduce the wear on the action because the spring tension takes up any slack in the mechanism, and thus reduces wear on bearing surfaces when the gun is fired.

Assisted-opening Mechanisms

Assisted openers work only when teh gun is either cocked or not cocked, it does not assist opening in both states. In some of these designs the old idea of one lock being cocked when the gun is opened and one when it is closed was resurrected. The result is a less violent spring opening action but the guns are generally easier to close. Sidelock and boxlock variants exist. A classic example of an assisted opener is the 1906 Baker, used in the Lancaster ‘Twelve Twenty’, the Grant ‘Lightweight’ and the Churchill XXV ‘Premiere’.

Published by Vintage Guns Ltd on (modified )